Exerting too much effort to complete a certain task is not uncommon. This is characteristic, especially of people who are habitually contrarian. Ideally, one exerts the least amount of effort possible to achieve the highest yield possible, but for various reasons, this is difficult to pull off. Hence, knowing, (1) when to exert effort, (2) how much of it to exert, and (3) the way in which it should be exerted, is necessary for optimal exertion. I will attempt an exploration of these three questions, but we must begin by defining effort and its result, which I will refer to as yield.

What is Effort?

Effort can simply be defined as the expenditure of energy—physical, mental, or both. Since energy is a limited resource, one should use it sparingly.

What is Yield?

Yield is the result of exerting effort. Positive yield produces desirable outcomes; negative yield produces undesirable ones. Yield seems to be a multifaceted sum consisting of tangible benefits that are achieved immediately after the exertion of effort and other components which may include ethical benefits, prospective benefits, and aesthetic benefits. I’m sure there are others I overlooked.

Since effort and yield have been defined, we can finally discuss the first facet of effort exertion: whether to exert effort.

Exert Effort?

The first question helps determine whether a certain task requires one’s effort—that is, whether one’s effort is warranted.

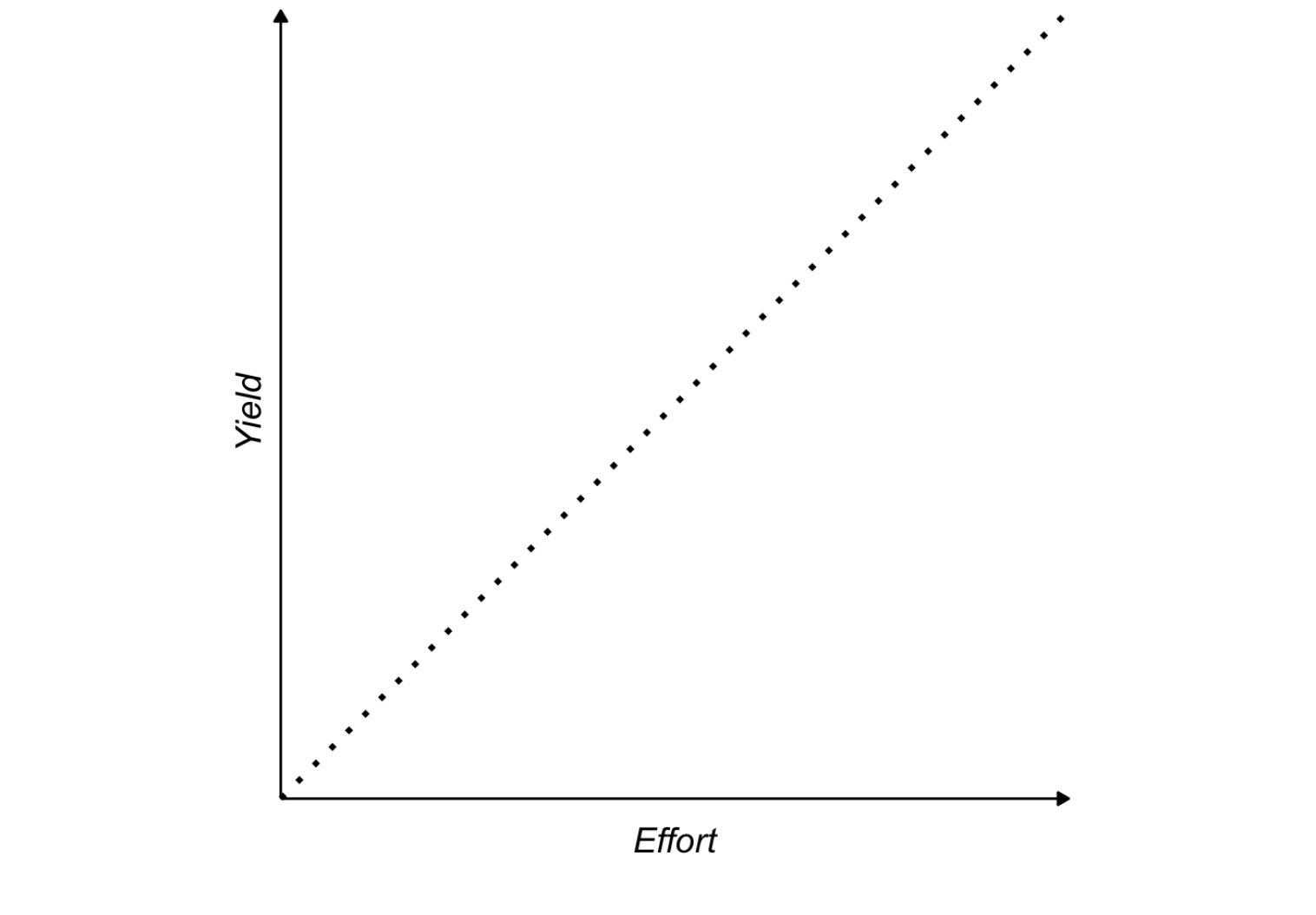

It should be obvious that negative yield is not worth exerting effort for, so we will continue our discussion under the assumption that we are guaranteed positive yield. Take a look at Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Effort vs Yield

Anything below the line should be considered a waste of effort, and anything above it should justify effort. One should desire low effort and high yield (above the line). By the same token, high effort and low yield are undesirable (below the line). Our goal is the lower the effort-to-yield ratio as much as possible.

Where one draws the line for making an effort may vary based on one’s values and the anticipated consequences, but the idea should be pretty straightforward. In the subsequent section, I explore the extent of effort exertion and its justification.

How Much Effort to Exert?

The second question helps determine whether the amount of effort exerted is proportional to the yield.

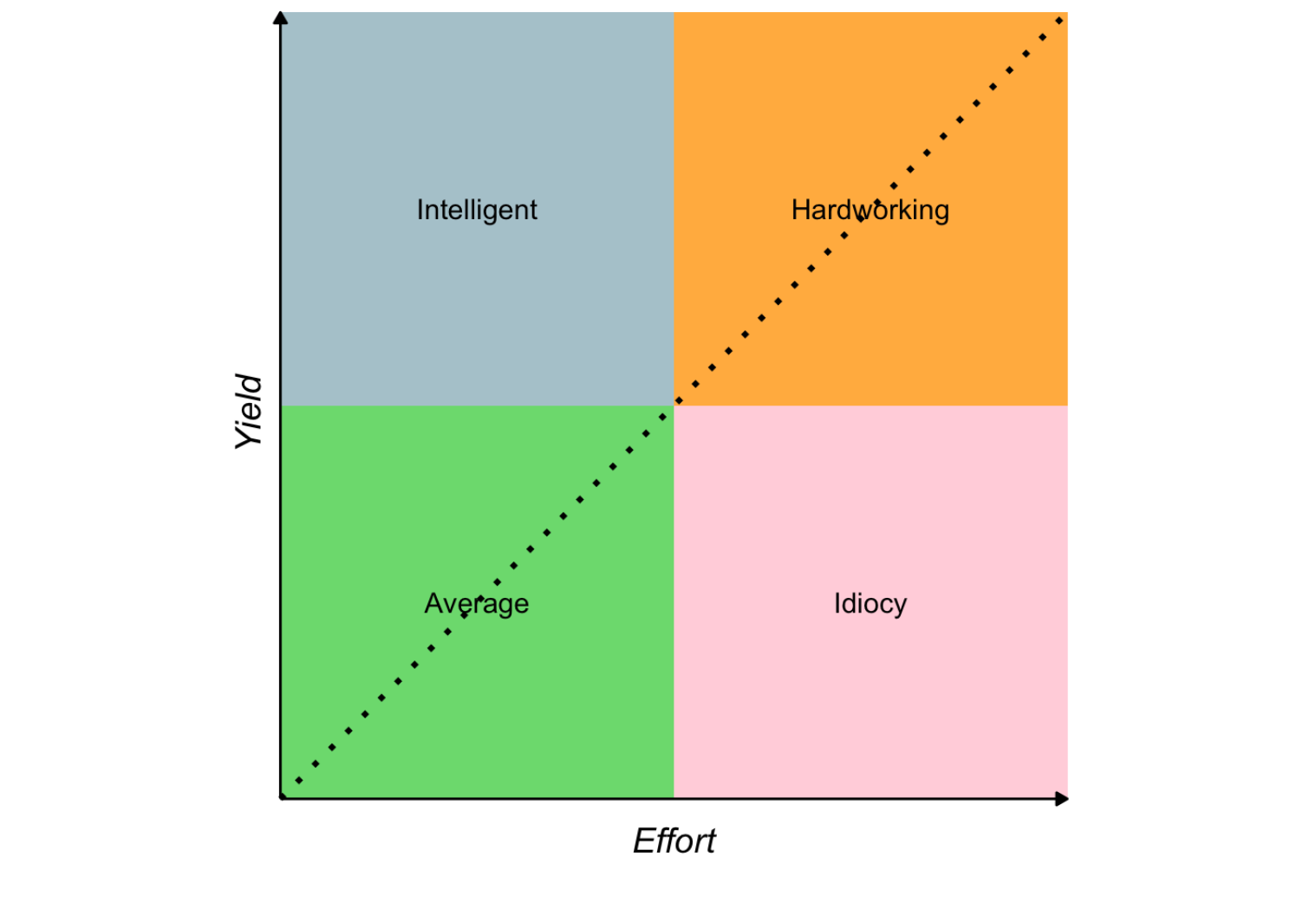

We can further divide the plot into four distinct domains of behavior. Take a look Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Classifications of Behavior Based on Effort and Yield

The intelligent person is able to achieve above-par results while investing a low amount of effort. This is the ideal situation to be in. The hardworking person expends more effort to achieve comparable results to the intelligent person. Hardworking people compensate for their lack of talent and intelligence by investing a higher amount of effort into the task. This behavior is often considered a virtue by propriety, though this plot aptly illustrates its drawbacks. The average person achieves disappointing results and, being lazy, also invests little effort. At this point, it should be pretty obvious why idiocy belongs to the corresponding category. Any amount of effort that results in negative yield would also belong in this category.

The plot does a decent job of illustrating the faults of an inflexible educational system, or really, any kind of bureaucracy. In education, the ultimate goal is learning. From Figure 2, it can be gleaned that being hardworking is not the only way to achieve high yield, or to learn successfully, in the case of education. It would follow that there are other better, more intelligent methods of learning that require less effort from the student. However, educators often fail to question the value of their methods, instead allowing their curricula and attitudes to fall in the hardworking category, or worse, the category of idiocy, requiring students to adopt learning strategies—often assignments—that, in reality, do not help students learn at all, and instead waste time for everyone involved.

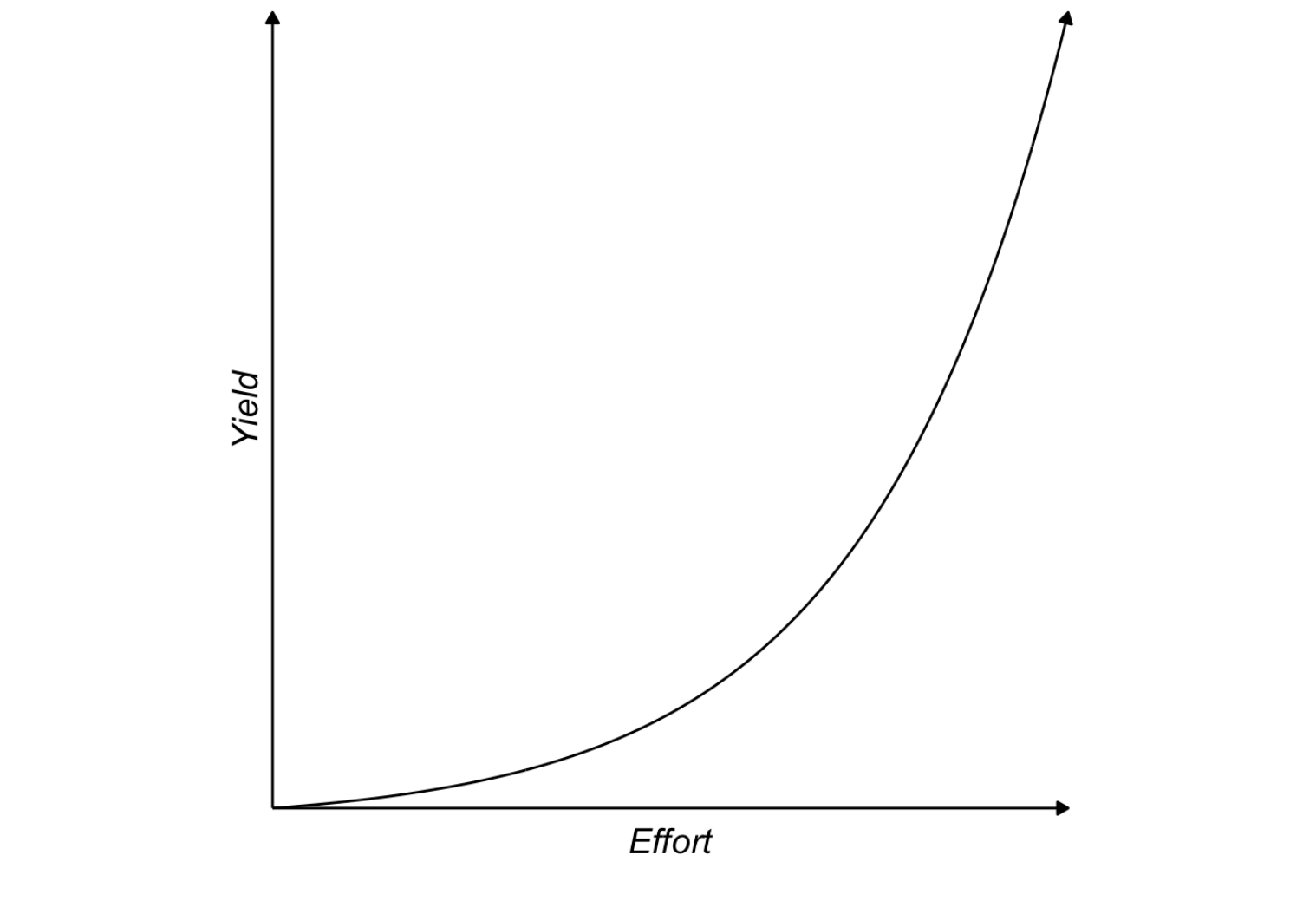

After reading the first version of the essay, Visruth proposed the following figure.

Figure 3: Effort and Yield per Effort

He posited that ideally, as one increases effort, the yield per unit of effort should also increase. That is, an increase by one unit of effort at low effort should not give the same yield increase compared to an increase by the same unit of effort far to the right side (high effort). As one increasingly invests effort, a higher rate of yield increase should be expected.

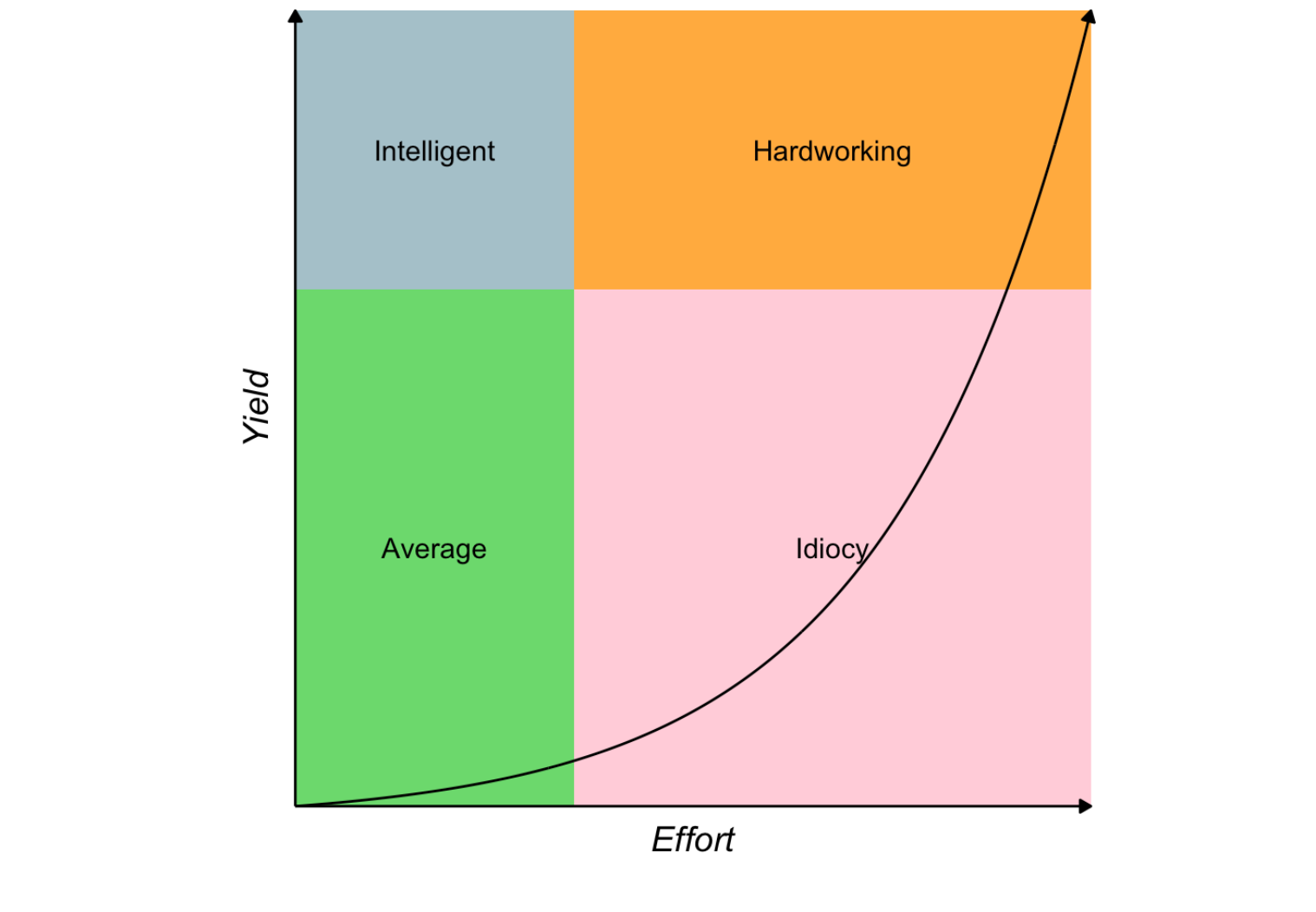

Collating these thoughts yields Figure 4.

Figure 4: Summarized Plot with Classifications of Behavior Proportional to Curve

Now that we’ve explored the idea of how much effort to exert, it’s natural to discuss how it should be exerted.

How Should Effort Be Invested?

The third and final question determines how, specifically, effort should be invested to achieve the highest yield possible.

We want the highest yield at the lowest cost of effort. When one finds themselves in a high-effort and high-yield scenario (hardworking), attempting to move toward the left category is imperative. One should ask themselves whether there is any method of decreasing effort without impacting yield. Laziness can sometimes be a virtue; lazy people ask themselves this question constantly. The problem is, lazy people also lack discipline by definition.

Changing one’s approach to a task has the potential to increase yield. In other words, regardless of how much effort is being exerted, as long as one’s methods fail to change, increasing yield is impossibly difficult. One should pivot paths before trying harder. That is, it is important to realize that effort has little bearing on yield.

Last modified on 2025-09-28